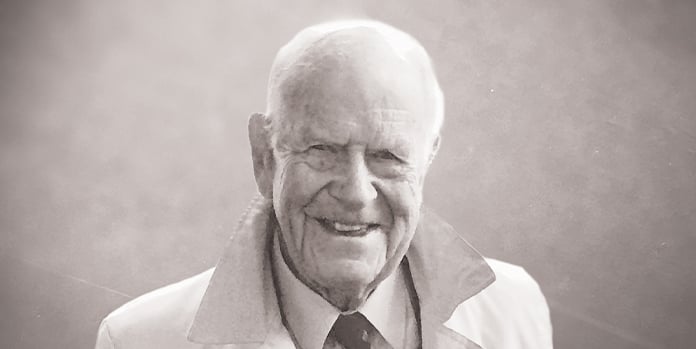

It may be difficult for us to imagine a time when Australian children could be mistreated without ramifications. But this is exactly the society in which Dr Bob Birrell OAM (OM 1950) began his work as a paediatrician. Over the decades to come, he would work tirelessly to change attitudes and practices, ultimately making the world a safer place for all children.

A tragic case leads to a lifetime of advocacy

The son of a tough, charismatic WWI veteran, Bob Birrell went into medicine at the urging of his father. With his heart set on a role at the Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH), Birrell began his paediatric career there in 1958. In was during this first year, working as a Junior Resident, that he encountered the case that would change the course of his life.

This shocking case involved an infant admitted with frost bite, a fractured femur, pressure sores, malnutrition, anaemia, and evidence of past fractures. After five months’ rehabilitation, the boy was sent home, only to be readmitted twice more with injuries that could not be explained. The young child died a few hours after his third readmission, and Bob was “devastated”.

“[I] could not see how these problems could have developed by accident,” he said in 2017, adding that further investigation was “vigorously discouraged” by fellow RCH staff.

Galvanised by this tragic case, Bob worked with his brother, police surgeon Dr John Birrell (OM 1941), to write two landmark papers documenting cases of child abuse, which were published in 1966 and 1968. Both included undeniable photographic evidence of each case, and their recommendations including the reporting of all suspected cases of child abuse to a central agency and bringing the police into hospitals where cases of abuse were being treated.

“We realised very early one of the main reasons why the maltreatment syndrome is not well-recognised is the general attitude of disbelief and incredulity that people would or could do such things to little children,” the brothers wrote. “This attitude is widespread, extending to housewife, doctor, lawyer, and even policeman.”

A new community and overdue recognition

It would take many more years of difficult advocacy work, conducted alongside Birrell’s demanding hospital schedule, before any policy changes were made. “At the time, [the brothers] were not believed and there was strong opposition to police involvement from Bob’s seniors,” the RCH now states.

In 1974, approaching exhaustion after 17 years at the RCH, Bob decided to move his family to Gippsland. His intention was to raise cattle and enjoy a slower pace, but as the Latrobe Valley’s only practicing paediatrician, his schedule soon became as demanding as it had ever been.

“He was always available, taking calls all night and working all day,” remembers his son, Peter Birrell (OM 1985). “Like many people who’ve had a significant impact on the world, he had a strong desire to make things right. He was a very forceful personality, and perhaps this made him unpopular with the powers that be, but he was beloved by the people he helped. His patients knew they were getting an extremely high level of care.”

“Bob Birrell has effectively been a prophet without honour in his own medical community,” stated RCH Alumni President Dr Kevin Collins in 2017 when presenting Birrell with an award for exceptional contributions to paediatrics. “I, together with our alumni colleagues, thought it was time to right this wrong, and for Bob to enjoy this recognition.”

In 2001, Bob was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for his work in the field of child abuse. His legacy includes today’s practice of mandatory reporting, and the establishment of early hospital child protection units.

Peter sums up his father’s legacy, when Bob died in 2021, by saying: “He saved countless children’s lives by shining a light on something very few were prepared to face.”