American political scientist Francis Fukuyama’s oft-referenced End of History thesis, introduced in a 1989 essay that coincided with the last throes of the Cold War, argued that Western liberal democracy had triumphed as the final form of human government. His Whiggish interpretation declared that there was no viable alternative to liberal democracy, and yet, thirty-five years later, according to the Economist Intelligent Unit’s 2024 Democracy Index, globally fewer people live in a full, functioning democracy than at any time since the Index began in 2006.

A recently published ACARA1 2024 National Assessment Program Civics and Citizenship Report found that Australian school students’ civics understanding was also at its lowest level since records began. Alarmingly, this is occurring at a time when there has been a significant rise in both misinformation and disinformation, notably online, and an increasingly uncivil tenor is apparent in ever more polarised political discourse. It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that a recent report from the University of Cambridge’s Centre for the Future of Democracy found that it is among 18 to 34 year-olds that satisfaction with democracy is in sharpest decline.

This confluence of alarming trends should act as a clarion call to the critical role that education plays in producing informed and engaged citizens to act as a bulwark against democratic backsliding.

Education is key to building civic leadership

The idea that democratic resilience relies on educated citizens is not new; both Aristotle and 17th century English philosopher, John Locke, emphasised this point. John Dewey, the late American philosopher, believed that an informed electorate, nurtured through education, is vital for a thriving democracy.

Today, there is a patent need for young people to not only become politically literate, but just as crucially to develop the broad range of thinking skills required for civic leadership in the twenty first century. At Melbourne Grammar School we want our holistic education to produce independent, ethically reflective and informed citizens who see the value of civic service and can hold considered, nuanced opinions.

It is essential that students are equipped with an understanding of the machinations of political systems and the varying interests and perspectives of political actors, but equally that they appreciate the significance and evolution of democracy itself.

A liberal education should engender dynamic and flexible thinking and be unapologetically intellectual. Rich opportunities should be afforded in and out of the classroom to allow young people to engage with difference and complexity.

Students should think critically, ethically and globally. They should be taught how, not what, to think, so that they are comfortable in the grey, analysing a plurality of perspectives, and only then are they able to proffer substantiated opinions. But just as importantly, teachers must not shy away from contentious issues for fear of causing offence; for what message would that send to the next generation? Being comfortable with being uncomfortable should be a necessary tenet of any flourishing classroom.

Students must come to understand that the content of the historical source or literary text only be processed once its provenance and purpose have been established, an approach that enables them to better navigate the fragmented and largely unregulated online news ecosystem.

The next steps towards a liberal education

John Dewey wrote a century ago that “Democracy has to be born anew every generation, and education is its midwife.” Current trends provide a salient reminder of this. Indeed, earlier this year in passing a resolution on the relationship between democracy, human rights, and the rule of law, the United Nations Human Rights Council emphasised the important role for education in strengthening “democracy, good governance and the rule of law at all levels.”

Opening next year, Melbourne Grammar School’s Centre for Humanities will provide a world-class home for the teaching of a broad range of related subjects, thereby creating a central space where the respectful contest of ideas will be a daily norm. This underscores Melbourne Grammar’s continued commitment to the value of a liberal education at a time when it has never been so crucial.

Nick Young

Head of Humanities

About Nick Young

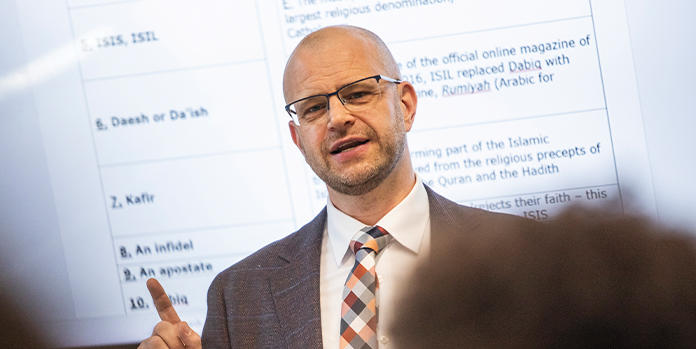

A Humanities teacher for almost 20 years, Nick Young commenced at Melbourne Grammar School as Head of Humanities in 2025. He joined us from Mazenod College where his roles had included Dean of Digital Pedagogy and Head of Humanities. Prior to this, Nick held senior positions including Head of History and Politics at several international schools.

Nick holds a bachelor’s degree in social and political sciences from the University of Cambridge and a postgraduate degree in education from the University of Oxford.

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority ↩︎