Each year, Senior School students present a production – usually Shakespearean – outdoors in the Quad, taking full advantage of the unique bluestone setting. Students from Melbourne Girls’ Grammar normally form part of the cast.

This year there was a new spin on an old favourite – Romeo and Juliet. Here, Senior School English teacher, Charles Chambers, reviews the production.

Our Scene

The divided streets of fair Verona have laid their scenes on Brunswick’s Sydney Road for the 2022 Quad Play. The shop signs lining the lockers are impressive during school hours in their mundane authenticity, but by magic hour as the stars emerge, they come to life with full storefronts.

There’s the gorgeously garish ‘Nails 4 U’; the opaque pawnbroker where all is ‘Bought & Sold’; the aptly titled ‘Arranged Bride’; the Friar’s neon-lit ‘CBD Dispensary’ that does not stand for Central Business District; Capulet’s eye-watering pokies bar and underage club, and a faded greengrocer that looks to have stood the longest. An expansive Montague Real Estate board looms at the edges. While the generational tension of the original play eyed the advance of enlightenment, this version faces the steadier march of the north side’s gentrification.

The Players

Here our warring families are both alike in dignity insofar as neither have it. The Montague boys prance in pastel polos and windcheaters worn like capes, while a smarmy Lord and Lady Montague—sensitively embodied by Patrick Bolton and Chloe Waddell—console each other in wounded self-righteousness. The local Capulet boys are indelicate larrikins draped in polyester; Hugo Hughes’ Lord Capulet stalks in a Neville Bartosesque jumpsuit while his insouciant wife, captured with apt heedlessness by Emma Taylor, totters in platform heels, fur coat and platinum bangs, lending the impression she enjoys her wines.

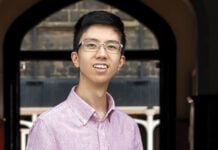

Amidst their feud our star-cross’d lovers unite as young alternatives in the modern Brunswick scene. Romeo struggles to find his place as the angsty emo-hipster of his conservative friends and family. Juliet is like a Skins character, complete with punkish green and magenta streaks and hot pink headphones. Both are convincingly rendered by Jack Flintoft and Esther Nastri, who imbue their misfit roles with raw, impulsive fervour. Nastri has the talent to cut through her cool and flippant exterior with the sudden knife of pain; the tears leap to her eyes. The two leads fly, often in an instant, between comedy and pathos, carrying the thrust of the story all the way beyond their final stop at the tram station for Shakespeare Grove (a nice touch).

The surrounding players are as vivid in their performances. Tom Carne’s Tybalt seethes with indignant rage, Hal Porter’s Mercutio with unhinged irreverence. Jack Straker’s Benvolio undermines his cousin’s stubborn melancholy by taunting him on his fixie bike. Tom Reith provides an interesting gender reversal, transforming the Capulet nurse into Juliet’s camp bestie. This is not an attempt at Shakespeare where one wonders whether the cast understand their lines.

The Stage

Director Belinda Annan also ensures the space is used to its full potential. An uncomfortably familiar night club scene for Capulet’s party unfolds in a Tarot-like series of dancers along the Coleman Room windows. Careful lighting guides us from one emotional beat to the next as we whisk through time and space.

Perhaps most impressive is the production’s care to evade all too familiar comparisons with Baz Luhrmann’s film. The opening brawl, springing from an overture of overlapping street talk, is quick to remind us this is not 1996, but indeed the 2020s; the plague is COVID and the Prince a celebritised politician. Even arranged marriage is given new meaning in the strategic courtship of #Paris’ social media fame, which Felix da Silva Clamp pilots with skilful tone-deafness.

In one of this adaptation’s more inspired choices, #Paris’ interactions with the Capulet parents and his prospective Juliet are mediated entirely through phone stream, calling forth the emptiness of modern relationship structures. His reaction to Juliet’s death is even played as glee, no doubt at the thought of his own audience growth.

Romeo and Juliet was always meant for crowds not altogether generous with their attention spans. That it has kept three full houses screwed to their seats is testament to this production’s success at retaining the burning heart of Shakespeare’s text. The entire cast, crew, string quartet and production team should feel proud of breathing new life into a tragic world where love has long sold out, and violent delights reign supreme.